A pill to cure all ills? It’s just in our heads

Published 12:00 am Thursday, July 5, 2012

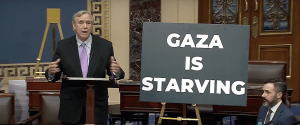

- At the National College of Natural Medicine, patients are prescribed a variety of therapies, including herbs, that might enhance the placebo effect.

• Researchers say the placebo effect can be just as good as real thing

In a defining moment of the 1999 movie “The Matrix,” rebel leader Morpheus offers a choice of blue pill or red pill to Neo, played by Keanu Reeves.

“You take the blue pill and the story ends. You wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe,” Morpheus explains. “You take the red pill and you stay in Wonderland.”

Neo’s choice is between knowing the truth or remaining ignorant but happy. It’s a choice increasingly confronting health care providers as new studies, some using a variety of imaging technologies, have begun to substantiate one of medicine’s great mysteries: the placebo effect.

Brain scans are showing not only that patients given placebos experience similar effects to those given traditional pharmaceuticals, but also that, in some cases, measurable chemical changes are taking place in the patients’ brains that mimic the changes produced by medications.

Last month, dueling commentaries in the Hastings Center Report, a national journal devoted to the ethics of medicine, highlighted the dilemma: if patients can heal better and faster just by the power of belief, how much do their doctors have to tell them?

The American Medical Association code of ethics says physicians must tell patients when they administer placebos, but most physicians know that telling too much will decrease the placebo

effect.

Healing vs. full disclosure, or informed consent. Blue pill vs. red pill. Trying to enhance healing without resorting to deception requires a great deal of nuance, say a number of Portland doctors.

Oregon Health & Science University neurologist Barry Oken received federal funding between 2004 and 2009 to study placebos. Oken focused on the expectancy effect, the idea that simply expecting to get better helps patients get better.

In one study, patients with Parkinson’s disease responded to placebos with improved motor skills. In another, obese patients were provided lifestyle counseling and pills they were told were weight-loss supplements. In reality the pills were placebos — sugar pills. The patients did not lose weight.

In a third study, Oken and colleagues were able to reproduce the placebo effect in laboratory mice.

Crossing the line

But in attempting to study placebos with Alzheimer’s patients, Oken confronted an ethical impasse. First, he recruited 40 elderly subjects who did not show signs of dementia. For two weeks they were given a sugar pill and told it contained an herb that might help their brains. The following two weeks they were given no pill.

Researchers administered a series of tests for brain aptitudes such as memory, ability to pay attention and reaction time, and found that participants improved after the sugar pills.

If a placebo could help seniors think better, Oken reasoned, might it help seniors with early dementia? The only way to study that was to reproduce the experiment in seniors with early-stage dementia. He recruited nine subjects, but during a debriefing with one of the early subjects he was confronted by a spouse who didn’t like her husband getting a sugar pill for two weeks when he was already suffering from dementia.

Oken thought about the woman’s comments and called off his study.

She was right, he decided. Giving a placebo to study people with no dementia was OK, but giving it to people who already had the disease — even if it might help them — felt unethical.

“I crossed some line with this person being my patient,” Oken says.

Size and color

In research, deception is allowed under strict guidelines. But in everyday practice, deception involving placebos is much trickier. Oken points to a 2008 study in which physicians were asked if they would give a patient a sugar pill for fibromyalgia, a little-understood chronic pain disease. Only 10 percent said they definitely would not.

Another study asked physicians how often they recommended treatment primarily intended to enhance patient expectations, and only 20 percent said never.

But the placebo effect is about much more than sugar pills, Oken says.

“If you ask any surgeon, they know part of surgical improvement for low back pain is placebo,” Oken says. “You go up to people and say, ‘This procedure is likely not going to help but has a 20 percent chance of help.’ Or, do you say, ‘This surgery may help your outcome.’ The better surgeons know how to work it to maximize placebo effect.”

Patients can even experience nocebo, or a negative placebo effect, according to Oken. Told in lurid detail all the possible bad side effects from a therapy, they are more likely to have them.

What Oken tries to do is tailor his approach to individual patients. For those who want to know everything, he tells everything, or close to it. Others don’t need the details and want to trust him more, so he tells them a little less.

And while, outside of clinical studies, nobody is handing out sugar pills to patients — too deceptive — Oken says there are more than a few dietary supplements that might come close to that description.

Oken teaches OHSU medical students about the placebo effect in the hope that they can better control for it in studies. For example, he says, researchers have found that the size and color of a sugar pill affect how well it works, so studies measuring a medicine against a placebo have to make sure everything matches.

Not a bad word

Heather Zwickey, dean of research at Portland’s National College of Natural Medicine, says that much of naturopathic medicine is indistinguishable from the placebo effect, and it would be unethical to not offer placebos to patients who might be helped.

Naturopathic therapies, Zwickey says, are provided as part of a holistic treatment program that can include diet, touch and encouragement from a naturopath who spends an hour or more with each patient.

“Some people might think of these as placebos,” Zwickey says. “For us it’s therapy.”

Zwickey collaborated with Oken’s research center in reproducing the placebo effect in mice. She took mice who had a form of multiple sclerosis and each day injected into them a compound that alleviated their paralysis. Then she replaced the compound with sugar water, but continued the injections at the same rate. The mice continued to get relief from their paralysis after the placebo shots.

“We didn’t think of this as having a placebo effect,” Zwickey says. “There’s something going on at a level of the brain where we’re so used to thinking things, that our brains do it for us.”

Portland psychologist Beth Darnall treats amputees with mirror therapy. By using mirrors daily so that a reflection tricks their brains into thinking there are two intact limbs rather than one, amputees are able to dispatch phantom limb pain. Darnall has no problem admitting mirror therapy, which includes relaxation exercises, is all in the heads of her patients.

In fact, Darnall is concerned that changes in health care marketing during the past two decades may be making it nearly impossible for drug companies to conduct valid studies of new medications. The drug companies may have unwittingly enhanced the placebo effect for everybody.

She cites a Journal of Clinical Psychiatry study published two weeks ago concluding that in drug trials, placebos were working as well as many of the new drugs being developed to treat schizophrenia. That could be a result of people’s changing attitudes toward pills in general, Darnall says.

Up until about 20 years ago, pharmaceutical companies didn’t advertise new drugs on television or in newspapers. They marketed directly to the physicians who did the prescribing. Consumers weren’t bombarded with the idea of pills as panaceas.

“Maybe they’ve done such a good job of promoting this fallacy that a pill can cure everything and the populace has believed it to such an extent that they have undermined themselves and the research domain,” Darnall says. “People see all these commercials: ‘You’re sad, take a pill.’ So you enroll people in a study and you offer them a pill. Of course it’s going to help.”

If all that advertising has made people more susceptible to placebo healing, Darnall is all for it.

“Placebo is not a bad word,” she says. “Somewhere along the way it became pejorative. People say, ‘You do that, but that’s just placebo.’ If the end result is the desired outcome, in what world could that be bad?”

OHSU neurologist Erin Klein’s favorite placebo study involved MIT researchers dividing participants into two groups. One group was told they were being given a $2.50 pain pill. People in the second group were told they were getting a discounted 10-cent version of the pain pill. The pills were actually identical placebos.

All the participants were administered mild, pain-causing electrical shocks before and after they took the pills. But more of those given the “expensive” pills reported their pain was reduced after taking the fake medication.

Nature’s cure

Klein says that patients suffering dementia are especially difficult to study. Many elderly patients think they are seeing the first signs of Alzheimer’s, he says, when in fact anxiety and depression are impairing their memory.

A placebo, Klein says, might be changing a patient’s depressed attitude, but might appear, in a clinical test, to be changing how well the patient thinks.

And yet Klein says maximizing the placebo effect could be especially useful in neurology because of the lack of effective therapies for many who suffer brain maladies such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. But there’s a danger in using placebos and later telling the patient.

“You potentially undermine this person participating in future research because they no longer trust the researcher,” he says.

Unbridled optimism might not always be a plus in patients, says Lynn Jansen, associate director at the Center for Ethics in Health Care at OHSU.

Jansen headed a study published this year that involved interviewing cancer patients enrolled in phase-one trials and found a majority had “unrealistic optimism” about what the study might do for them. They had been told the early- stage trial was intended to find out only whether a compound was safe, but when interviewed, many participants confided they signed up believing it might help them heal.

Such unrealistic optimism, which Jansen says is different than the optimism of a generally positive outlook, could mean patients didn’t truly take in the informed consent process when it was explained to them.

In some cases, patients with unrealistic optimism about one therapy might put off important alternatives, Jansen says.

“Most people when they hear optimism think it’s always a good thing,” Jansen says. “Our study was showing, not so fast, it’s not always good. It sometimes can be questioned ethically.”

Craig Fausel, gastroenterologist and chief executive officer of the Oregon Clinic, says irritable bowel syndrome is a classic diagnosis that encourages doctors to consider the placebo effect. Physicians have no test to pin down the cause of the stomach pain and other symptoms, so there is no targeted cure. Some doctors will prescribe anti-depressants to tamp down the body’s pain response, and others will try anti-spasm medications.

“Most of these don’t really have any true benefit over placebo,” he says. “But the placebo effect is huge.”

Fausel says he prefers not to prescribe medication for irritable bowel syndrome, but when he does, he faces an ethical struggle.

“It’s worthless if you present it to a patient (as), ‘I don’t think it’s going to work, we’ll give it a try, but what’s the use?’ What I try to do is say, ‘For some people this works really well,’ ” Fausel says.

Sometimes, Fausel says, encouraging a placebo response is the best a doctor can do.

“Voltaire once said, ‘The art of medicine consists of entertaining the patient while nature cures the disease.’ Well, there you go,” he says.