In beautiful color: ‘Psychedelic Rock Posters and Fashion of the 1960s’

Published 12:15 am Monday, October 14, 2024

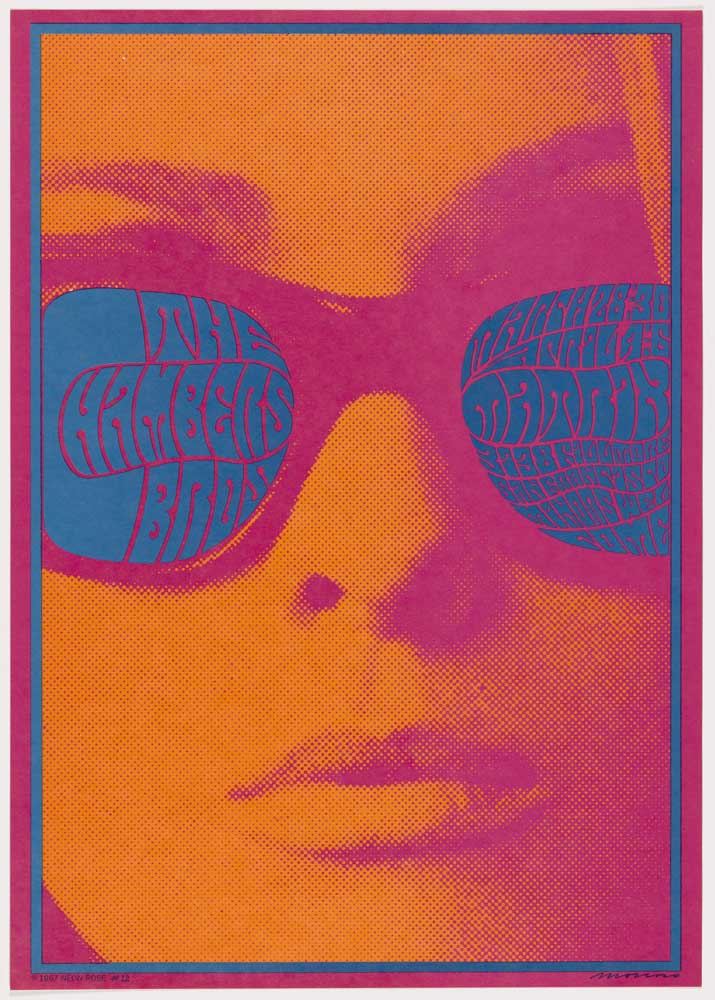

- One of the more well-known artists: Victor Moscoso (American, born Spain, 1936), The Chambers Brothers, March 28-30, April 4-6, 1967, The Matrix.

Perhaps people of all generations will appreciate the art and creativity in the new Portland Art Museum exhibition, “Psychedelic Rock Posters and Fashion of the 1960s.”

Trending

The exhibit, Oct. 19-March 30, features some 200 posters made for concerts in San Francisco and elsewhere, along with some fashion items. It focuses on the main artists and their extravagant creations of the era, and Mary Weaver Chapin, PAM’s Curator of Prints and Drawings, hopes people of all ages enjoy the exhibition.

“About a year ago, I showed the images in a binder to my daughter and her friends — three high school students,” she said. “They didn’t know any of the bands, but they responded to the graphics. That gave me hope.

“We don’t want to appeal to just aging hippies.”

Trending

She added: “I’m really curious. I think we’ll get people coming for a lot of different reasons — they’re people from the ‘60s, or maybe their parents listened to the music, or folks are interested in it from a design point of view. There’s a lot of interest in the fashion — we’ll have 21 fashions on display.”

In the mid-1960s, music promoters Chet Helms and Bill Graham recruited young artists from San Francisco to make distinctive posters for their music venues, the Avalon Ballroom and the Fillmore Auditorium, respectively. Artists wanted to portray the “heady experience” of music and life at the time through a graphic language to communicate the excitement of rock concerts.

They would use French Art Nouveau designs, Wild West posters, Victorian engravings and Renaissance art and combined them with witty and provocative design. Chapin called such artists “thieves” in a good way. She’ll hold a discussion Oct. 20 at the museum titled “Beg, Borrow, and Steal: Crafting the Psychedelic Poster.”

From publicity: While deploying distortion, pattern, and surrealism, they juxtaposed heterogeneous objects to mimic the “psychedelic experience,” in which participants sought to access a realm of thinking beyond the visual world, typically through the use of LSD.

Artists fed off the trend through friendly competition. They included Rick Griffin, Alton Kelley, Victor Moscoso, Stanley Mouse and Wes Wilson — the “big five” of poster design — as well as Bonnie MacLean (Graham’s wife), Jim Blashfield and Bob “Raphael” Schnepf — all young, teenage or 20-something artists at the time.

Schnepf actually lives in Milwaukie. While he entered the poster-making scene later than the others, “what he did was outstanding,” Chapin said. “Bob was great at lettering.” There are some of his works in the exhibition, including a poster for The Doors and other bands.

Maybe the most recognizable poster is the “Skeletons and Roses” Grateful Dead poster by Mouse and Kelley. They would go to the San Francisco Public Library to uncover old images in books, and for “Skeletons and Roses” they found source material and added color.

“Everyone thinks of this as a great original design,” Chapin said. “They were wonderful ‘thieves.’” They and others wouldn’t really worry about copyright violations, because the posters simply didn’t have much shelf life to warrant litigation over legal rights.

“Not that they were imitating these things, they were transforming them,” she added.

Pulsating color combinations played a key role. Moscoso, who trained under renowned color theorist Josef Albers at Yale University, once said, “The musicians were turning up their amplifiers to the point where they were blowing out your eardrums. I did the equivalent with the eyeballs.”

There were posters made in Portland at the time for venues such as Beaver Hall, Pythian Hall, Springer’s Ballroom and Masonic Temple, the latter of which happens to be part of Portland Art Museum campus. Some will also be on display in the exhibit.

The exhibition’s posters are from the time period 1966 to 1971, and gifted by Gary Westford, who serves as a consultant to the project.

And they are indeed works of art, Chapin said.

“That’s how I’m presenting them, as important artifacts of design. It’s marvelous to investigate them in this way,” she said.