A balancing act as the river flows

Published 5:00 am Monday, March 3, 2025

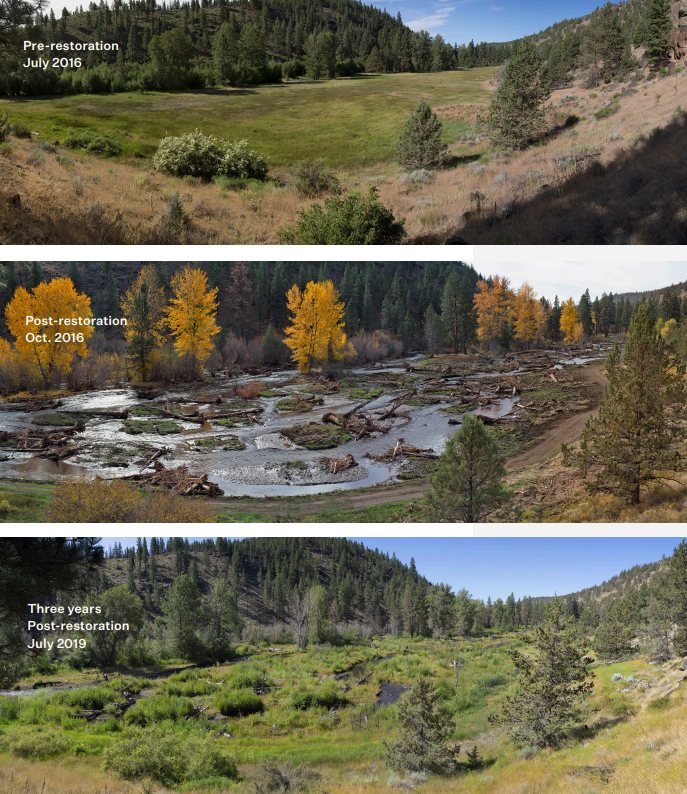

- The Whychus Canyon Preserve Restoration Project was supported by the Pelton Fund from 2014 through 2018 and restored abundant and complex habitat along a mile of Whychus Creek. This area is critical for all life stages of newly reintroduced Chinook salmon and steelhead trout

The relationship between the Deschutes River and the three dams that it flows through in Jefferson County has been complex since the dams were built in the mid-1900s.

Trending

For decades after the dams were built, there was no mechanism for fish to travel through the hydroelectric project. A system for fish capture was installed in 2010, called the Selective Water Withdrawal tower. PGE and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, who jointly own and manage the project, have celebrated record fish returns since its installation.

However, environmental groups have raised concerns the SWW is having a negative effect on the Lower Deschutes, claiming it has led to rising water temperatures and unsafe pH levels.

This controversy comes as nonprofits, environmental groups, and many Tribes are pushing for dam removal across North America. Along the Klamath River, four dams are set for removal, the largest dam removal project ever in the U.S. A total of 79 dams were removed in the U.S. in 2023, according to nonprofit American Rivers.

Trending

But the relationship between the CTWS, whose land the dams reside on, and the hydroelectric project is unique. Only two other Tribes in the U.S. has ownership stake in a hydroelectric dam, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, who purchased full ownership of the Kerr Dam in 2015, and the Seneca Nation of New York are on track for full ownership of hydroelectric dams on their land.

For the Tribes, the dams represent financial sovereignty and stewardship.

“Taking care of the river and the land, the water, the fish, that’s part of who we are,” said CTWS general manager of natural resources Austin L Smith Jr. “The dams were built at a time when we as a tribe had very little, and the partnership offered us a way to fund ourselves. My grandfather and father, uncles, helped build the dam, there is a lot of pride in it, even as we know now the impact it has on the river. This partnership lets us be stewards of the river and the fish.”

The history

Pelton Dam was finished in 1958 and Round Butte Dam in 1965 while the reregulation dam downriver from Pelton was built in 1955. They represent the largest hydroelectric project entirely within the state of Oregon. The Pelton and Round Butte dams were owned and managed by PGE for decades. The reregulation dam is fully owned by the Tribes.

When the dams were built, fisheries, camps and sites along the Deschutes River were flooded. “I hear stories of families that had their fishing villages upriver, and those spots are not accessible anymore, we lost access to that,” said Smith.

In 2001, the Tribes bought partial ownership of the project, and in 2022, the Tribes purchased a larger interest, now holding a 49.99% interest in the dam. The Tribes will be able to purchase another .02% of the project in 2036, which would give them majority ownership. For the Tribes, the increase in ownership meant more say in the operation of the dam, and more leverage in decisions about the dam.

“We’re at the table able to make decisions and push for projects that support better stewardship of the entire river system,” said Smith. “Our people have been through so much displacement, and poverty and struggle. Our ancestors had their apocalypse. Now we are building a better future for ourselves, the river, and the people to come.”

Reintroduction

The reintroduction efforts of the dam didn’t begin until almost 50 years after the dams were built. A fish ladder system was designed when the dams were built, but never succeeded in allowing fish transportation, and their implementation was abandoned. In 2005, dam relicensing efforts led to an over $100 million investment in fish passage.

In 2010, the Selective Water Withdrawal Tower was implemented as part of the dams recertification process, which required them to improve fish passage.

The controversial tower circulates water from different depths of Lake Billy Chinook in an effort to better acclimate fish as they’re transported, and to regulate downstream temperatures.

No current system for fish to naturally travel around the dams exists, migratory fish are captured at either end of the project and transported to the other side. Smith says a better fish-passage system is of high priority to the Tribes.

“Seeing the fish return to the river is what we want,” said Smith. “The fish are our livelihoods, our first foods. They are sacred to us, and we are pushing to better support their return across the entire watershed.”

This year, PGE numbers show the largest steelhead return since the reintroduction program began. It’s broken this record each year since 2022. This year, they’ve seen over 900 steelhead return.

For the Tribes, the sovereign right to fish and manage resources on their lands is an important way of life. Smith says the reintroduction efforts in recent years have brought back fish the Tribe was not accessing locally anymore, even if their efforts are not complete.

“When we have meetings and ceremony now, we have fish that are from our waters,” said Smith. “Elders talk about a time when they had no fish for ceremony and meetings. Even though it’s slow, to have one fish lets us feed our people. That’s a big part of why we advocate for even more reintroduction efforts.”

Marked by controversy

Some environmental groups do not share the same optimism in the success of the SWW and the increase in fish returns as PGE and the Tribes. The Deschutes River Alliance, a Portland-based nonprofit that self-monitors water quality in the Lower Deschutes River, says water temperatures in the Lower Deschutes have been too warm for 297 days over the last 12 years, and over the past eight years the standard pH of the river has been exceeded 75% of the time.

They argue the SWW’s blend of water from different depth includes more water from the warmer Deschutes and Crooked River arms of the watershed, which also include more pollutants than the cooler and less polluted Metolius arm.

“The tower has been a colossal failure. Not only has it passed few salmon or steelhead above the project, but the change in flow regimes has also made water quality in the lower river much worse, with devastating consequences,” said DRA in their 2024 State of the River report.

The DRA has fought the SWW in court, suing PGE in 2016. Courts ruled in PGE’s favor. DRA later appealed, and the case was dismissed.

“My husband and I have been rafting the Deschutes for 30 years,” said Maupin Mayor Carol Beatty in a press conference about the impact of the dams on the Lower Deschutes. “We see more algae and fewer fish. Maupin is a charming community, full of kind and caring people. Part of what makes that so is the river. It means jobs for guides, and they bring their clients. It means tourists who don’t fish or raft but just want to hike or camp along the river. It means all kinds of jobs for high school and college students in the summer. They all bring so much to our town. The dams are damaging our river. I don’t know how you get around that.”

A recent story from the Oregon Journalism Project focused on the outcry of advocates, including DRA among other community members, of the Lower Deschutes River. PGE and the Tribes say there’s more to the picture.

“The story is not one of an electric utility, its critics, and the health of the Deschutes River. That framing is too narrow. The real story is one of tribal sovereignty, resilience and self-determination. To be precise, the sovereignty of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs is the real story,” said J. Garret Renville, chairman of the Coalition of Large Tribes, who wrote a letter in response to the story.

PGE and the Tribes say their work has included significant effort to improve the health of the entire Deschutes River Basin, not just below the dams. The Tribes and PGE have spent over $27.5 million across 58 habitat projects along the river system.

“We believe that our efforts throughout the Deschutes basin will increase the availability of fish for communities along the entire river, both upstream and downstream of the project,” said PGE in a release.

Alongside restoration efforts, PGE and the Tribes conduct monitoring across the entire river system. They conducted a multi-year water quality study across the river that was completed in 2019.

“Ultimately, the study showed that current operations – with a commitment to ongoing adjustments supported by data – offer the best balance available,” according to a PGE release.

For the Tribes, the impact of the dams greatly changed the river, and decades without fish passage led to years with very few fish returning upriver. Warm Springs has a vested interest in the health of the Lower Deschutes River, through historical connection and stewardship, as well as the fact that their drinking water intake comes from an oxbow of the river below the dams.

“The dams have had a negative impact on the river historically,” said Smith. “Having no fish returns for decades had a big impact on our people, our livelihoods, our connection to our land. We’re working now to try and improve and be stewards of the river, but it takes time. If we could return the river to its history we would, but that’s not feasible.”

Financial Impact

The Pelton Round Butte project is a big financial driver across not just the Tribes, but Jefferson County as well.

In Jefferson County, PGE is the largest property taxpayer, making up 17% of the taxbase in 2023. Taxes paid by PGE fund over $2 million a year for schools, as well as large funding amounts for tax districts like the county library, MACRD and COCC.

The Tribes also have a significant financial benefit from the project. PGE pays them for their share of the generated electricity, which they then sell primarily to Willamette Valley patrons. The dams provide power for 150,000 homes across the state.

In 2023, records show PGE paid the Tribes $47.3 million for their generated electricity.

“As a sovereign government, we don’t have a tax base that collects property taxes from out residents the way most governments do,” said Smith. “We have to develop other ways to fund our work, which includes things like infrastructure, housing, community events, health services, basically everything we do, we have to find funding for.” Smith also noted his job is largely funded by the money the Tribes make from the hydroelectric project.

The project also employs over 100 people in Jefferson County. Its impacts create even more jobs and significantly boost region tourism. The reservoirs it creates make up Cove Palisades State Park’s Lake Billy Chinook and Lake Simtustus, which offers a variety of recreation options, and drive many to visit Jefferson County each year.

The future

The relationships government entities, corporations, community members and nonprofits have with the hydroelectric project create a vast tapestry of impacts, controversy and proposed solutions to problems around the dam. The Tribes and PGE offer optimistic views of the potential future fish returns and water health of the river, now that new systems are being created.

Meanwhile, environmental groups, and many citizens in general, raise alarm bells on water quality in the Lower Deschutes. The overarching current reality: there is more to do to manage and protect the natural resources of the Deschutes River.

“We have been stewards of the land since time immemorial, and we will be stewards of the land forever into the future,” said Smith. “It’s all about balance. We have to advocate for what is best for our people, the land, the water, and the fish, all at once. It’s a balancing act, managing all the different voices, but I’m hopeful.”

“Our ancestors had their apocalypse. Now we are building a better future for ourselves, the river, and the people to come.”

– Austin Smith Jr., CTWS general manager of natural resources