How Portland’s hidden neon shop is keeping the city bright — one tube at a time

Published 5:00 am Thursday, May 15, 2025

About 20 paces into the Southeast Portland home’s backyard sits a dwelling slightly larger than a standard shed. Inside: Glowing, vibrant neon signs depicting green skulls, palm readings, skateboarding slang, dining room directional and more.

It’s Nigel Barnes and Jen Casebolt’s backyard where they run their business, Electric Spaghetti Neon. The two work to craft new, and restore, true neon signs — not the LED knockoffs found on Amazon.

“The technology is crazy and esoteric,” Barnes said. “Then there’s the artistic part to it. Every time I light it up, I’m like, ‘Wow, that looks great,’ and it does the magic thing.”

Electric Spaghetti Neon might sound like a convoluted business name, but in context, it’s straightforward. Electric describes the electricity component, spaghetti describes the texture of the glass when heated, and neon, well, they’re neon signs.

Barnes has more than 20 years of experience working with the tubes of glass. Some of his most recent work can be found at Bar Hollywood, 4128 N.E. Sandy Blvd., which opened its doors on Wednesday, April 23.

In 2024, Barnes worked on about 50 neon signs in Portland, not including the rest of his restoration projects. Making a sign can take anywhere from hours to days to weeks depending on the scale of the project, and if the materials are accessible.

Glass tubes, filled with gas, are heated up to about 1,500 degrees, shaped, and zapped with immense amounts of electricity, giving bright reds, blues, golds and more that people see radiating from businesses.

Nigel Barnes, owner of Electric Spaghetti Neon, shows a neon sign that he restored for a restaurant in Medford.

Getting to Portland

Barnes grew up in Denver and was always keen to the arts, exploring drawing, painting, playing music — think synthesizers and “creepy and weird” sounds — and skateboarding as a means of expression.

“It’s a big part of my identity,” Barnes said of skateboarding and punk rock. “It ties in with neon in a way because you have to do your own thing and figure out how to do it yourself.”

Inside the shop is a “push mongo” neon sign, which refers to the skateboarding technique of using your front foot to push the board instead of the back foot.

He later attended School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Pacific Northwest College of Art.

“I dropped out both times, once wasn’t enough, I had to drop out twice,” Barnes said.

He moved to Oregon in 1990 because his mother relocated to Southern Oregon.

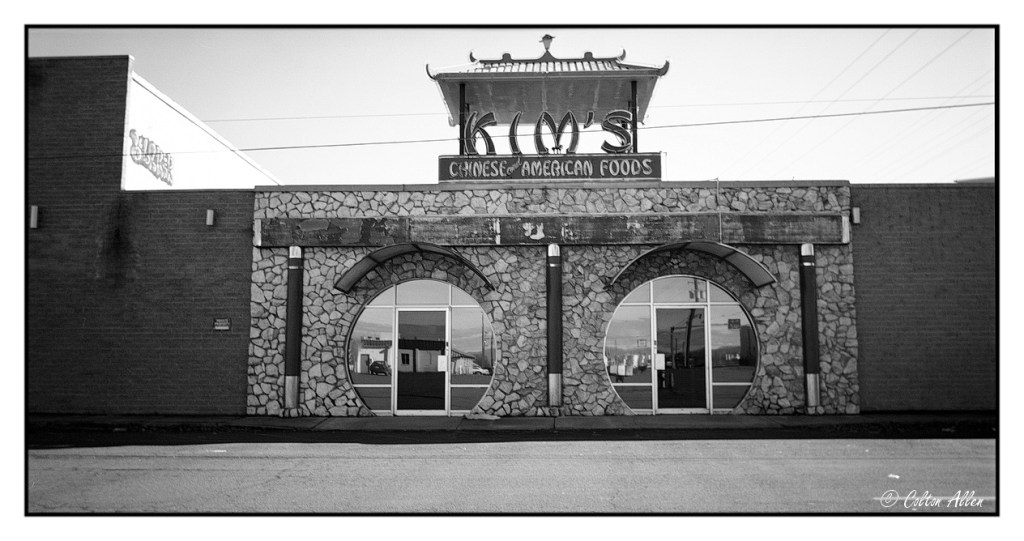

Barnes and Casebolt met at 17 years old in Ashland. Their first date was at Kim’s Restaurant – the only option for Chinese food in the area – and the first place they fell in love with neon.

“We were already appreciating it,” Casebolt said of their budding love for neon, holding up an old photo of Kim’s she took about 30 years ago.

The couple moved to Portland in 1996 and have lived in the Woodstock neighborhood ever since landing in the Rose City. They’ve lived in their current house for 21 years, after living in a rental near Woodstock Elementary School.

An old image of Kim’s Restaurant in Medford. Oregon. (Flickr, courtesy photo)

A love for neon

Barnes’ love for neon came to him when he worked as an antique dealer at Rejuvenation, a manufacturing company of lighting fixtures and hardware. Projects were done in-house, working on restoring furniture and light fixtures. He soon learned that glass bending is a specialized skill.

There, he met a man named Don, who was an old school neon bender. Over the years, Barnes and the crew worked on hundreds of restoration projects with him.

“I got increasingly interested in what makes ‘em work, how they’re put together, what are the details, why this glass versus this other one,” Barnes explained, sipping his sparkling water. “It’s an endangered craft.”

He couldn’t help but feel frustrated at the tedious processes, but he scored an apprenticeship with Don, opening opportunities to use his equipment and develop his glass skills.

After 18 months of consistent work, Barnes remembers feeling so “intensely frustrated” that he could not make enough bends in a row to create a piece of glass.

“Then, things started to click for me a little bit after that,” Barnes said.

His first restoration of a neon sign was a metal sign in the shape of a gift box with a bow on it. All it said on it was “Gifts” in big, blue lettering. Barnes spent months working on the five-letter project.

Casebolt said Barnes overcame his frustrations with the support of neon sign veterans.

Barnes and Casebolt are active in the Preservation Arts Guild, which specializes in historical preservation of craft, as well as the Neon Makers Guild, which supports fellow neon artists and works to educate about the craft.

The bright neon lights hanging on wall, silhouettes Nigel Barnes in the shed of his neon business, Electric Spaghetti Neon, in Southeast Portland.

Building a business — literally

They built their shop in the summer of 2022, sacrificing prime real estate, aka the sunniest spot in the yard, which could’ve served as a perfect gardening spot for Casebolt.

As soon as the fence door opens, neon radiates from the dwelling.

Casebolt and Barnes equipment came from three neon shops’ worth of tools. They sorted through, selecting the best, most salvageable items, and converted them into usable parts for their shop.

One of Barnes’ 90-year-old friends, who lives on the border of Northern Washington, sold off his trailer packed with old equipment. Some of their tools date back to the 1920s, but they work like a charm.

Electric Spaghetti Neon is about 50-50 restoration and new custom neon signs. Most restoration work they do is for collectors or old signs around town, such as the neon sign at The Vern.

The couple said many people don’t know the difference between calling something neon versus a true neon sign. Oftentimes, signs are called neon if they simply light up bright and are fun colors, though they’re most likely made from LED lights.

“It’s deceptive,” Barnes said. “It’s extra frustrating because there’s only a handful of people now that know how to do neon. We’re trying to keep this handmade, traditional art alive.”

While people might not know the difference while shopping online, the difference is ever apparent when seeing the signs in person. Neon signs can be seen miles away, while their LED counterparts can only be seen from about a hundred feet away.

“It looks different, it has a different character and it feels very genuine,” Barnes said.

Nigel Barnes, owner of Electric Spaghetti Neon, bends glass into shape May 7 to make a letter on a neon sign he’s making for a client.

Keeping neon alive

Barnes hopes to provide a mentee the chance to learn the ropes of neon.

He struggled trying to learn the skills on his own, while he had help along the way, it wasn’t consistent, leaving him to fill in the gaps.

The shop is small, but mighty, and Barnes said he would like to teach one-on-one workshops, and would consider a more formal apprenticeship option in the future.

“There’s still a lot of really great, old neon signs in Portland. We lose them even now at a shocking rate,” Barnes said. “Being able to help preserve those is really important to me.”

Find more about Electric Spaghetti Neon at instagram.com/electric.spaghetti.neon.