Underwater hockey makes a splash

Published 12:00 am Thursday, August 23, 2012

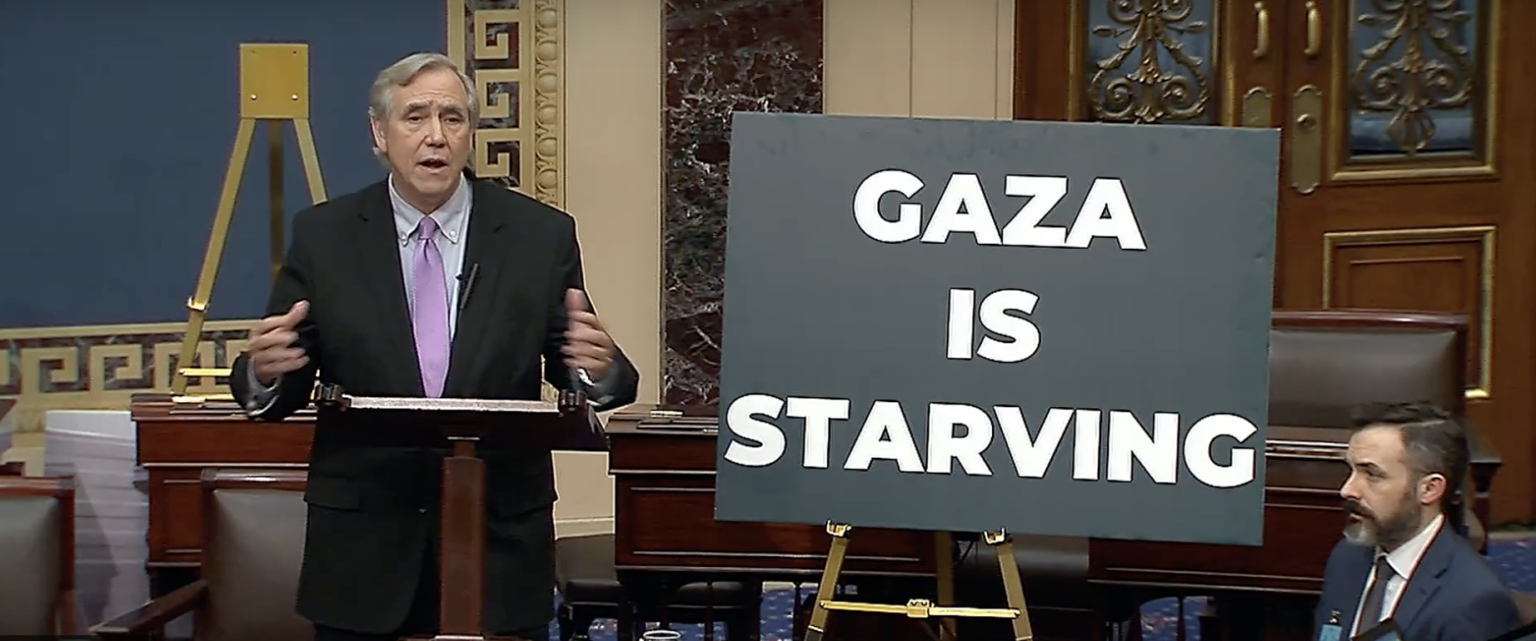

- Players (from left) Sandor Duis, Tania McLeish and Becky Jarnes get ready for an underwater hockey scrimmage at Mt. Hood Community College.

Imagine a fast-paced game of hockey. Players strategize, fight over the puck and sprint across the rink to score goals.

Trending

Now imagine doing it all while wearing flippers and holding your breath.

Underwater hockey sounds like a quirky, made-up sport straight out of “Portlandia.” Not so. Underwater hockey is a worldwide phenomenon, and it’s one of the most physically challenging games you’ll ever play.

It is not for the faint of heart.

Trending

Jorge Filevich started the Portland area’s first underwater hockey club about six months ago. He had played in his native Argentina since he took up the sport 19 years ago, and when he moved to Northwest Portland last year, he missed the game.

He started the club primarily so he could have people to play with on a team.

“It is a no-brainer,” he says. “It is the only way I would be able to play.”

He used Craisglist and Meetup to advertise the club, and on the first practice a mix of beginners and experienced players showed up.

Though most at the Portland club are beginners, experienced players come from around the world; the sport is popular in France, Australia and South Africa.

The club plays nearly every week at Mt. Hood Community College’s aquatic center, which Filevich chose in part because of the smoothness of its pool’s bottom.

“Everybody that has come try it loved it,” he says.

Lung capacity

Underwater hockey (also sometimes called, in the UK, “octopush”) has rules mostly similar to those of the sport’s terrestrial and frozen cousins. Six players on each team fight over a three-pound lead puck, using short wooden or plastic sticks to pass, push and shoot it into a goal area on the pool wall. Teams usually divide into “back” and “forward” positions, with no goalie. There are two halves of about 12 minutes each.

However, the puck lies below 6 1/2 to 12 feet of water, meaning players must hold their breath for long periods of time as they play it out. (The new Portland club, though, practices in water shallow enough to stand in, a welcome but discouraged relief for exhausted beginners.)

The lead puck does not travel far underwater on a single push, so players get up-close and personal as they nudge the puck along the floor, though physical contact is not allowed.

Players use snorkels to breathe without bringing their heads above the surface, so they can get air without having to take their attention away from the game. They usually only have time to clear the water from their snorkel (accomplished with a hard breath, which is more difficult than it sounds on an already-empty set of lungs) and grab one or two gulps of air before they have to plunge back down to rejoin the fray.

“The most difficult thing for me is building up my lung capacity,” says Becky Jarnes, a nurse anesthetist from Clackamas County who has played underwater hockey twice.

Jarnes is one of the beginners Filevich is hoping to recruit to the sport. She heard about it through a friend of a friend.

A college floor-hockey player and a longtime lover of “any sport having to do with water,” Jarnes says, “I had a hard time picturing the two sports melded together and wanted to experience it at least once.”

After an exhausting first practice, she was hooked.

“The more experienced participants were patient with the beginners and everyone just had a great time,” she says.

A pounding heart

Along with the physical demands of swimming hard without oxygen, there are strategic complications to snorkel breathing. If a player goes up for air too late, he or she can miss a chance to be open for a pass or to defend against an attack. But if the player goes up too long before a play, he or she might have to abandon a crucial scrum to go to the surface for a breath.

“Timing it just right and planning when to go under to help your teammate or being in just the right place for a pass is a learning experience I’m still working on,” Jarnes says.

These breathing challenges, combined with sprinting and the sudden changes of direction the game requires, make underwater hockey extraordinarily physically taxing.

“There’s nothing that’ll get you in better shape faster and without you even knowing it,” says Robert Hubbard, a regular at the club who has been playing for about 17 years.

Along with its daunting physical challenges, underwater hockey has one more unusual element: sound. While other sports come packaged with a set of characteristic sounds — the crack of a bat, a bouncing ball, a shouting teammate — the auditory world of the typical underwater hockey player includes little more than some slight stick-on-puck sounds and the player’s own pounding heart.

It means teammates have almost no means of communicating during play.

Sandor Duis is another regular at the Portland club with 28 years of underwater hockey experience. He has represented his home country of the Netherlands at European and worldwide competitions.

He puts it best: “It’s the most difficult sport, I think, in the world.”